The Handshake That Started It All

- December 17, 2025

- Words:

January 25, 1964. Saturday.

The Beatles registered their first number-one hit song in the United States: “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

And on a cold, rainy day in Portland, Oregon, a coach and his former athlete met for lunch at the Cosmopolitan Hotel to discuss a possible business partnership.

One hour later, Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman stood, reached across the table and shook hands. Blue Ribbon Sports was born.

To understand how two Oregonians arrived at that moment — and why it held — we have to go back a decade, to a teenager who had just been cut from baseball.

Phil Knight grew up in Southeast Portland and went to Cleveland High. As he tells it, he was the last cut on the sophomore-and-under baseball team — a decision that stung.

“I was heartbroken but my mom said, ‘You are not going to mope around the house. You’re either going to get a paper route or go out for track.’ Well, that was easy. I went out for track.”

That decision set him on a course that would change his life, and, eventually, the sports world.

Knight tried out for track and quickly found his stride. While he was physically smaller than his teammates, he was fast, competitive and willing to work.

At one early meet, his father, William, a labor lawyer who would later become publisher of the Oregon Journal, introduced him to Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman. The two older men had gone to college together at the University of Oregon. That day was his first introduction to the coach who would later shape his life.

By then, Knight was already starting to win and place in local races, enough to earn a name in Oregon’s competitive prep scene. During his junior year, he spotted a headline that stuck with him: Bill Dellinger, a runner from the University of Oregon, who had just won the mile at the national championships under Bowerman’s coaching.

“It was startling,” Knight said. “It was a huge headline in The Oregonian and that’s when I became aware of Bill Bowerman and what a phenomenal program he had.”

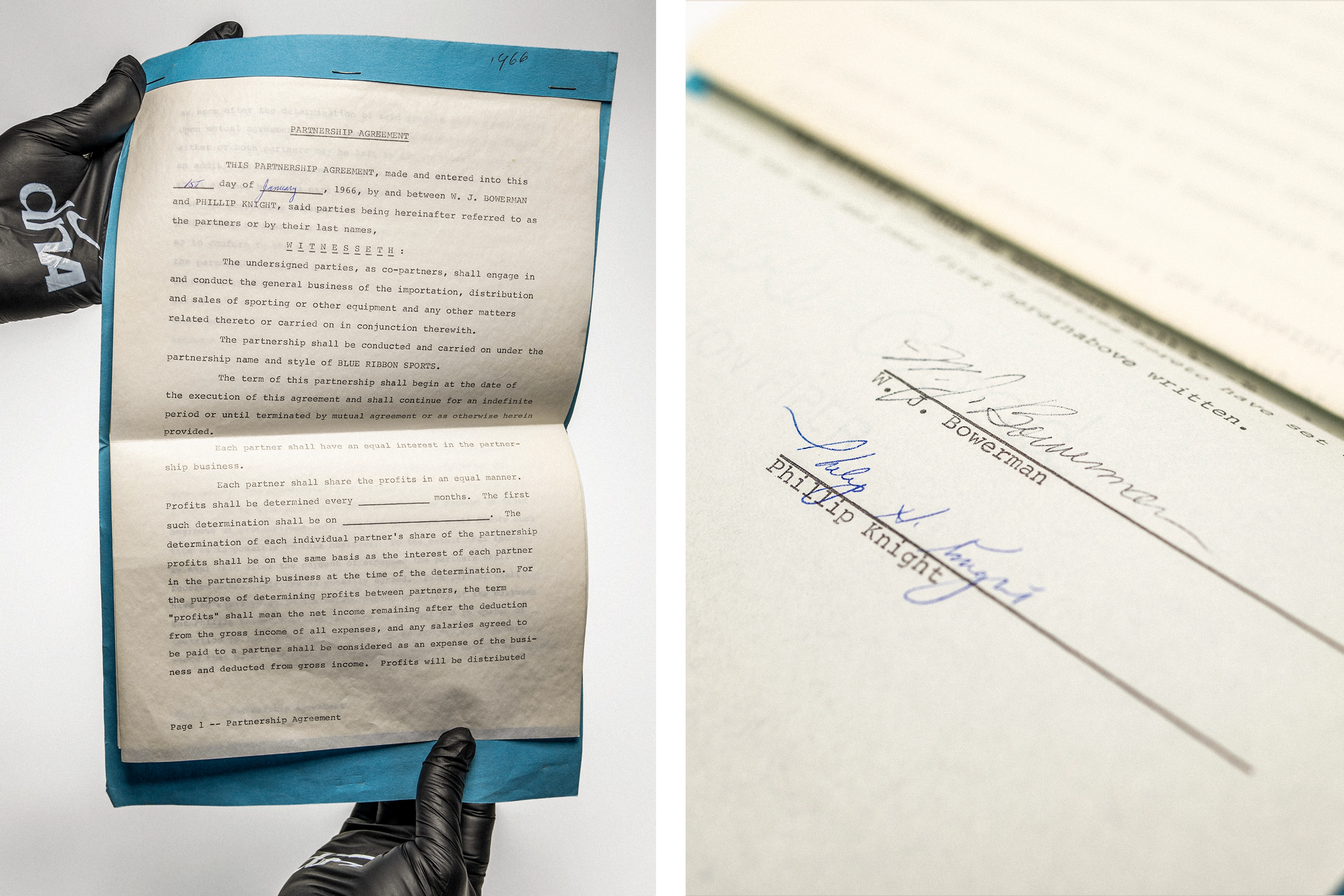

Two years after their handshake deal, Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman put ink to paper for their new business. This first signed contract is held in the Department of Nike Archives at PHK campus.

Although small and lean, Knight never let size hold him back. In 1955, he played on Cleveland’s city-championship basketball team, finished second in the league 880-yard run and took fourth at the state meet. By fall, he’d earned a spot on Bowerman’s track and cross-country teams at the University of Oregon.

Long before his first practice, though, his father had already turned to Bowerman for guidance — an early glimpse of the connection that would define both men’s careers. Curious to get the coach’s perspective on whether Phil should attend college or join the military, William Knight wrote to him that fall.

Bowerman replied with his trademark mix of bluntness and care.

“My first concern is for your young man’s education,” he wrote. “All will not be fun and frolic. It takes hard work for success in anything … it is a privilege to have your son here, also a responsibility for me, for you and for him.”

At left, Phil Knight at the University of Oregon Olympic Preview Meet in 1956; Knight competed after Bill Bowerman invited him to run the 400 meter. At right, Knight training while at U of O.

Like many freshmen before him, Knight soon learned what that meant, struggling under the bombastic Bowerman. “After my freshman year, I had to sit down with myself and ask if I was going to go back to that crazy man, or not,” Knight recalled. “I realized if I go back, I’m just going to have to do things his way because he’s not going to change. So I went back.”

That decision proved pivotal. Bowerman saw potential in Knight — not as a star runner but as an ideal test subject. “I wasn’t one of the best runners on the team,” Knight admitted. “Bowerman knew he could use me as a guinea pig without much risk.”

He called Knight the “hamburger” of runners — hearty stock, forgiving, determined — and began using him to test early shoe prototypes. In August 1958, Bowerman sent Knight a letter outlining his summer training plan and added a postscript: If you have a pair you think would make good flats, send them down. They’ll be ready when school starts.

The pair Knight received that fall featured an experimental white, rubber-coated fabric — “the kind you’d use for a tablecloth you could sponge off,” Bowerman later said. They were crude, functional and a glimpse of what was coming. The coach was still years from finding a manufacturing partner but his drive to build a faster, lighter shoe had already found its first willing tester.

These handmade track spikes are the oldest footwear created by Bill Bowerman in the Department of Nike Archives collection.

The spike is unique in many ways; its seamless toe box was built for comfort and fit and its minimalist design allowed just one seam, offset in the heel. The heel piece is made of sponge rubber.

By the time Knight graduated from Oregon in 1959 with a degree in business, his competitive drive had shifted from the track to the classroom. The next stop was Stanford where he enrolled to pursue his MBA.

At first, his path seemed uncertain. But during his final year, a class called “Small Business Management” caught his attention. It was a class that would quietly spark the idea of a lifetime.

“It was the only entrepreneurship class so it was one of the classes that I was most interested in,” Knight said.

He developed a strong rapport with his professor, Frank Shallenberger, who assigned the students a simple but open-ended project: invent a new business, define its purpose and create a marketing plan to support it.

Knight had recently overheard a conversation among photographers at the Oregon Journal, where he’d worked summers during college. They were talking about a surge of inexpensive Japanese cameras that were starting to rival the more powerful and costly German models.

“Electronics was a popular topic at that time and the smart kids chose to write about things like that,” Knight said. “But I didn’t know anything about electronics so I wrote about something that I did know about — shoes.”

Drawing from his experience as one of Bill Bowerman’s wear-testers, he built his hypothetical company. By 1962, German sports shoes were on the rise in the U.S. — high quality, yes, but expensive. Knight saw an opening.

He turned the idea into a paper he wrote almost literally overnight with a single bold hypothesis: Can Japanese sports shoes do to German sports shoes what Japanese cameras did to German cameras?

Knight argued that Japanese-made running shoes could compete on both price and quality with the dominant German brands. Knight received an “A.” When the assignment was over, he couldn’t shake the idea. “I wrote a letter of inquiry to virtually every Japanese shoemaker that I could find.”

Only one company replied: the Kow Hoo Shoe Company of Hong Kong. The letter, written in imperfect English, was polite but discouraging.

“It is with regret to inform you that due to lack of [such] equipment and material, we can hardly manufacture [such] type of shoes and trust that every shoemaker in Hongkong (sic) fails in doing so. We are expert in manufacturing Golf shoes, Skating boots and Bowling shoes etc.”

It wasn’t the answer Knight had hoped for, but it didn’t matter. A seed had been planted that would soon take root.

Shaken but not deterred, he was about to face the opportunity of a lifetime.

That story — and more — will come in future Department of Nike Archive features on The Record.