Inside the World’s Fastest Mile Race

- July 08, 2025

Words: Davis Jones

Images: Cameron Strand

To fully understand the look on Niels Laros’s face after narrowly clinching this year’s Bowerman Mile in Eugene, you have to go back to the ringing of the bell lap, when he still trailed the race leader, American Yared Nuguse, by more than three seconds.

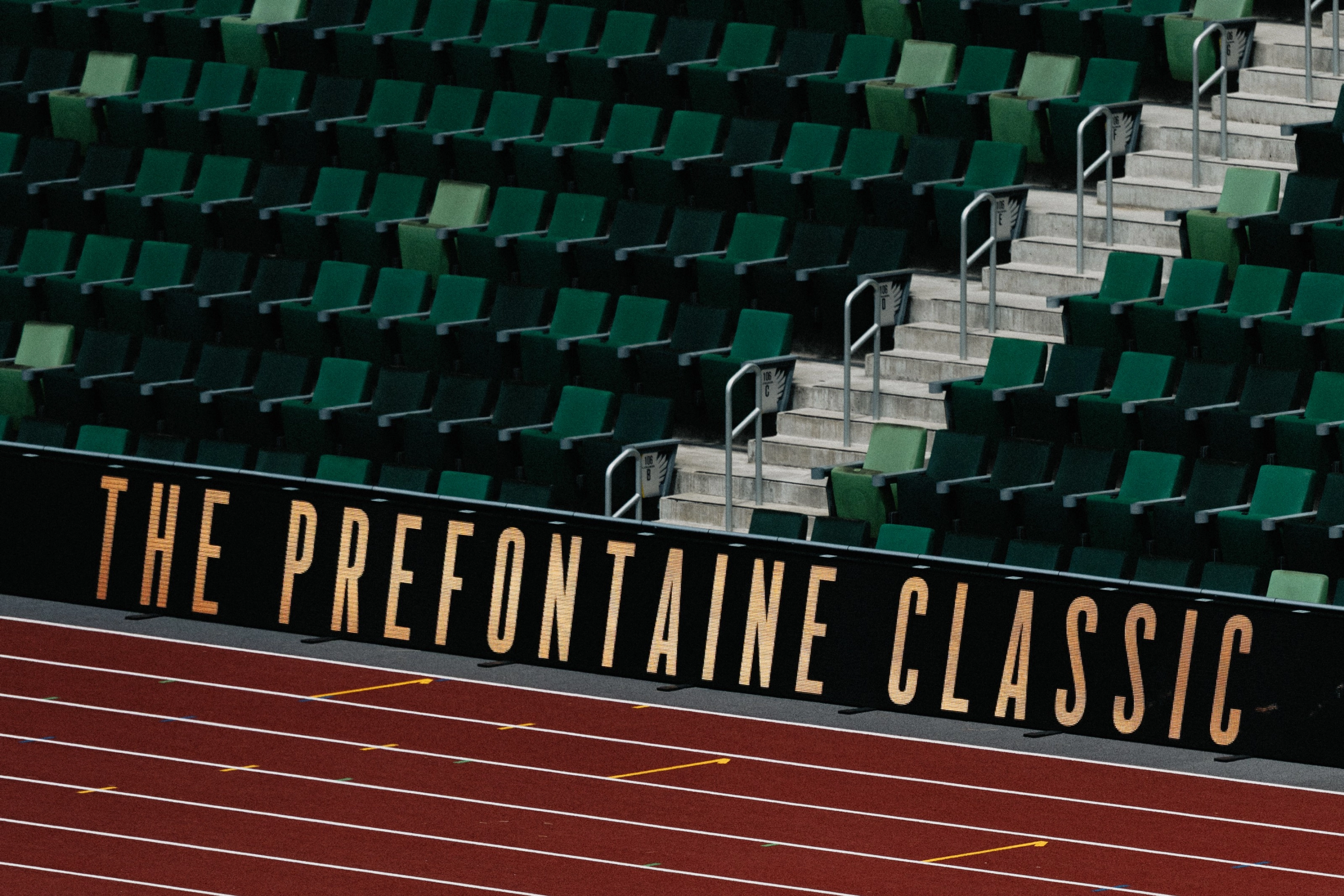

In front of a sold-out crowd in Eugene, Ore. at the 50th Pre Classic, the 20-year-old Dutch runner tapped into his own brand of Hayward magic. He separated himself from the chase pack with 400m to go. Then, at the final 200m mark, he took off for Nuguse, running an unthinkable 25.9 second split and making up an almost 8-meter gap in the homestretch. The two racers lunged at the finish line. A few seconds later, Laros saw the official time, wearing a look of disbelief: 3:45.94. He’d won the Bowerman Mile by one-one-hundredth of a second and set a new Dutch national record. His final lap — 53.3 — was one of the fastest fourth laps since the United Kingdom’s Steve Cram broke the world record in 1985.

“Man, that Hayward magic is real,” says Laros. “It’s a once in a lifetime feeling to experience a race like that.”

For 25 years, the Bowerman Mile has brought together the world’s most talented milers, assembling pros, world champions and Olympic medalists. The event is one of four premier mile races left in the world: the Dream Mile in Oslo, the Wanamaker Mile in New York City and the Mile Invitational in Iowa. Of those, it’s produced more sub-4-minute miles than any other race, counting 418 such performances to date, including this year’s race in Eugene.

Speaking of which, the 2025 race was arguably the deepest mile race in history, featuring the most men in one race under 3:50 (13), 3:49 (9) and 3:48 (8).

What makes the Bowerman Mile stand apart? Fast times don’t always correlate to a fast track. The latter can be an immeasurable mix of qualities tied to time, place and circumstances, leading to generational performances. But talk to anyone who’s competed in the race, and they’ll tell you: there’s something different about the Bowerman Mile.

“Man, that Hayward magic is real... It’s a once in a lifetime feeling to experience a race like that.”

Niels Laros, Nike athlete, Bowerman Mile

Year after year, the Bowerman Mile draws a stacked lineup, assembled with reigning world champions and record holders. Since 2000, it’s taken a time of 3:51.84 or faster to win the event. The race’s buy-in is all the more impressive considering that its results don’t count toward points at the end of the pro circuit, even though it’s classified as a Diamond League meet.

A runner who always circles the date of the Bowerman Mile is Australia’s Cam Myers, who finished sixth this year and set an Australian under-20 record with 3:47.50. In 2023, at just 16 years old, Myers ran as a pacer for Norway's Jakob Ingebrigtsen, who clocked the Bowerman Mile’s fastest-ever time in 3:43.73, setting a European and Diamond League record.

“We all want to win this race in particular,” says Myers. “It’s intensely competitive, and it’s the perfect environment for fast times.”

Whether or not a record falls at the Bowerman Mile, each year’s race teases out greatness in every runner, carrying the makings of a personal best.

“We all want to win this race in particular. It’s intensely competitive, and it’s the perfect environment for fast times.”

Cam Myers, Nike athlete, Bowerman Mile

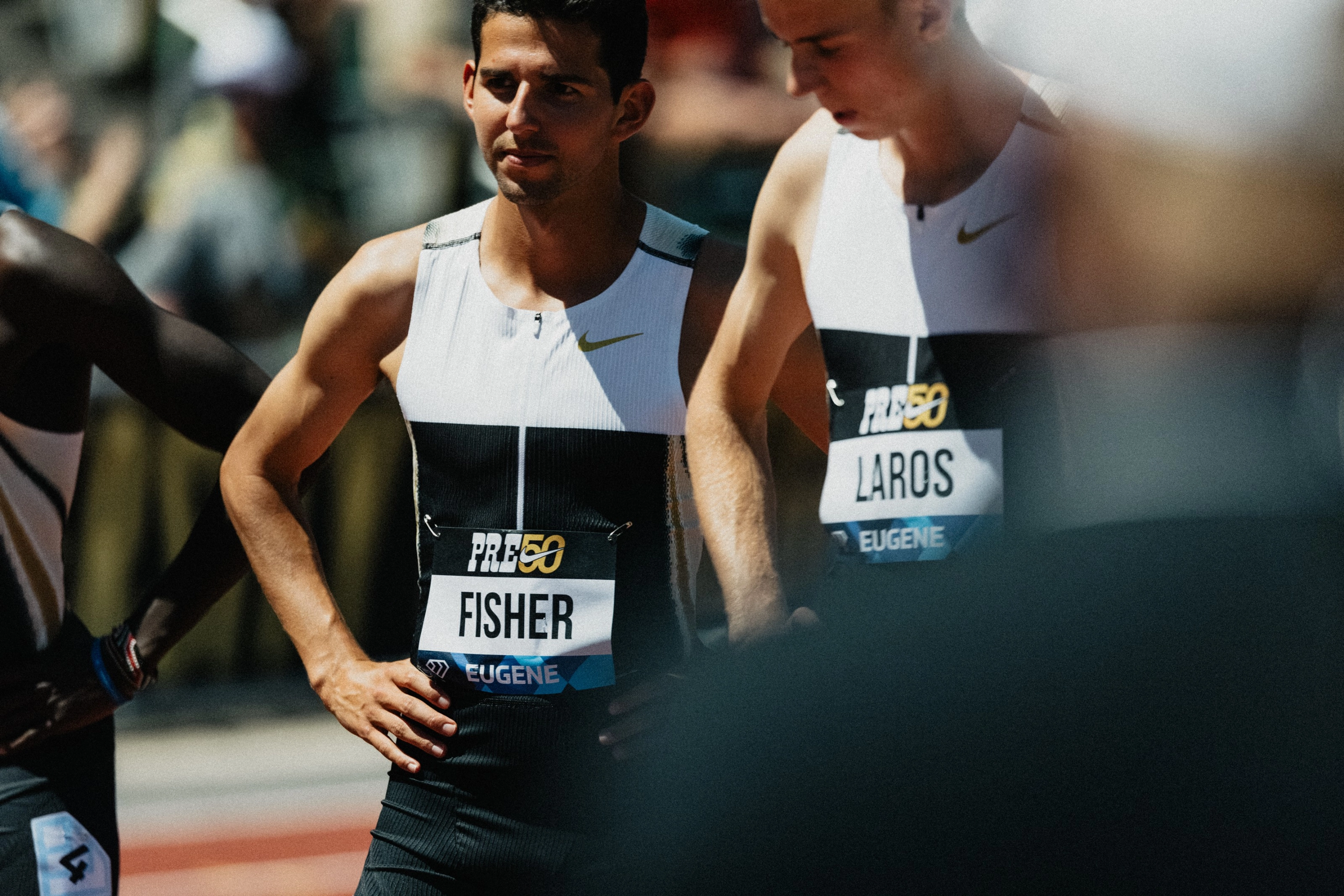

Grant Fisher, who holds the American Record in the 2-mile distance, ran his first Bowerman Mile this year, laying down a 3:48.29. The race is a self-fulfilling prophecy, he says. When racers know they are surrounded by a fast field, they all raise their game. Plus, the Bowerman Mile is almost always rabbited, or led by a pacer. Runners know they’ll get wrenched to their physical thresholds. Once the pacer drops, there’s no time to think. Just go.

“We all know the pacer is going to take us deep into the race,” Fisher says. “When the pacer drops, the field is of such high quality that these amazing times just keep rolling.”

“We all know the pacer is going to take us deep into the race. When the pacer drops, the field is of such high quality that these amazing times just keep rolling.”

Grant Fisher, Nike athlete, Bowerman Mile

“Every time I get the chance to run at Hayward, I remind myself to appreciate the moment, just because of the history that has happened there before me.”

Cole Hocker, Nike athlete, Bowerman Mile

Consider one of the Bowerman Mile’s most memorable performances — when Alan Webb, then a high school senior out of Virginia, broke the national high school mile record set by Jim Ryun that had stood for 37 years. The pacemaker took the first 409 meters at a searing 54.6, equivalent to a mile pace of 3:34.8.

At the race’s halfway mark, Webb had moved up from last place to 13th. The pace was brutal, and yet, with 400m to go, Webb remembers how his body felt loose, light and capable of much, much more. He began picking runners off on the backstretch. His turnover cycled with a power that outlasted men a decade older, who had competed for medals, who had set national records.

“Sometimes, the stars align in a race, and I knew this was one of those moments,” says Webb, recalling the moment. “When I got to that bell lap, I was able to find something in myself. Running the Bowerman Mile has that effect on people.”

The grandeur of the former Hayward Field, with its wooden grandstands and its Bowerman Building as the sentinel watching from the track’s eastern end, is different from how a spectator would describe the view from the updated stadium — a colossal venue built for the modern age. Webb remembers while he was barreling down the backstretch in 2001 how the extreme slope of the west grandstands gave the feeling that the fans “were right on top of you.” The passion and knowledge of the fans sitting in those seats rivals any locale in track and field.

“Even before Prefontaine, Oregon had a history of domestic milers who were very, very good, people like James Bailey, Dyrol Burleson and Jim Grelle back in the Bowerman coaching days,” says Pat Tyson, who ran for the University of Oregon in the early ’70s, where he was roommates with Pre himself. “The mile always had a cache among fans here, even before the Bowerman Mile officially began.”

Hayward Field is a place where fans take on the role of engaged sports scientist versus passive spectator. They’ll set their personal stopwatches to the smoke of the gun and scribble a runner’s splits in the margins of their program.

Kaarin Knudson knows. She ran for UO’s track & cross-country team from 1994 to 1999. A seven-time NCAA qualifier who won the NCAA’s Woman of the Year for Oregon in her senior season, she now serves as the mayor of Eugene. Her experience as a civic leader and a former athlete gives her a uniquely personal view on what makes Eugene’s passion for track so special.

“I have distinct memories while at UO of going on my easy runs and being stopped by community members, people I didn’t know; they’d congratulate me on a race I ran the previous weekend,” says Knudson. “When you’re an athlete, it’s motivating to be surrounded by a community who both root for you on race day and who recognize you when you’re ‘offstage,’ so to speak.”

Few competitors benefit from the Hayward energy quite like those who ran for UO during their college years — runners like Cole Hocker, who’s run his top three fastest mile times at the Pre Classic. During his rookie season in 2022, he donned the Nike kit in front of his home crowd for the first time at the Bowerman Mile. This year, he improved his personal best to 3:47.43.

“Every time I get the chance to run at Hayward, I remind myself to appreciate the moment, just because of the history that has happened there before me,” says Hocker.

The mile and its cousin, the 1500m, are separated by a little more than 100m. Depending on who you ask, the difference in how you run the mile compared to the 1500m is marginal. Webb jokes that you’re basically doing the same event, but the mile comes down to “who’s willing to suffer a little longer.” Others, like Laros, say the tactical game of the mile is slightly different than the 1500m. For him, the main difference comes from the start.

“Because you’re starting on the opening curve in the mile, you have less time to figure out your position before you need to tuck into the right spot,” says Laros. “You basically have to get shot out of a cannon and find a good slot so you’re not sorting it out on the corner and running a little extra distance.”

The cultural power of the mile gives it a revered place in the consciousness of running, along with the marathon. Both are niche distances in track and field, yet still count for world records.

The wonder of the mile might come down to its clean simplicity. Four laps. Taking the laps at one minute a piece add up to four minutes, considered the standard for the elite miler. The starting line is in roughly the same place as the finish. The same fans who cheer on the field at the gun are the same who cheer at the finish.

One could argue that the mile distance, in fact, was the spark that lit Bill Bowerman’s fascination with long-distance running performance. As a freshman at Oregon playing football, he met Ralph Hill, the first elite miler he befriended at the university. One day, Bowerman ran 400m around the track at an all-out sprint to test his speed. The clock read 63 seconds. Bill Hayward, UO’s track coach, leaned over and smirked. “Just so you know,” he said, “Ralph goes that fast for four laps.”

“Winning this race meant even more to me than setting the national record."

Niels Laros, Nike athlete, Bowerman Mile

Its relative scarcity at the professional level adds to distance’s mythical status. Pro runners don’t get many opportunities to compete in the mile. You might get a couple shots at it per year, between Eugene, Oslo and New York City.

“You can jump into plenty of 1500m races during the year. But it’s no guarantee you’ll get into one of these mile races on the pro circuit,” says Webb. “That’s assuming you’re healthy when your name gets called. If you get a chance at the mile, you better put it all on the line.”

That motivation fuels every competitor in the Bowerman Mile. From the young racer who’s traveling to Eugene for the first time, to the seasoned pro who wants to assert their world ranking, the Bowerman Mile summons a kind of communal willpower. For Laros, participation among those four laps, holding nothing back, is a rare privilege, one that can be tough to describe. Ironically, sometimes a fast time takes a backseat to the opportunity to step onto that 1609m starting line.

“Winning this race meant even more to me than setting the national record,” he says. “Obviously, running a fast time gives me a lot of pride, but taking the win here, at this place, was what I’m most proud of.”