Creating the Unreal: How Nike Made Its Wildest Air Footwear Yet

- April 11, 2024

On the second floor of the LeBron James Innovation building in Beaverton, Ore., Nike designers huddle around a table studying a 3D-printed shoe prototype for Victor Wembanyama’s size 21 foot.

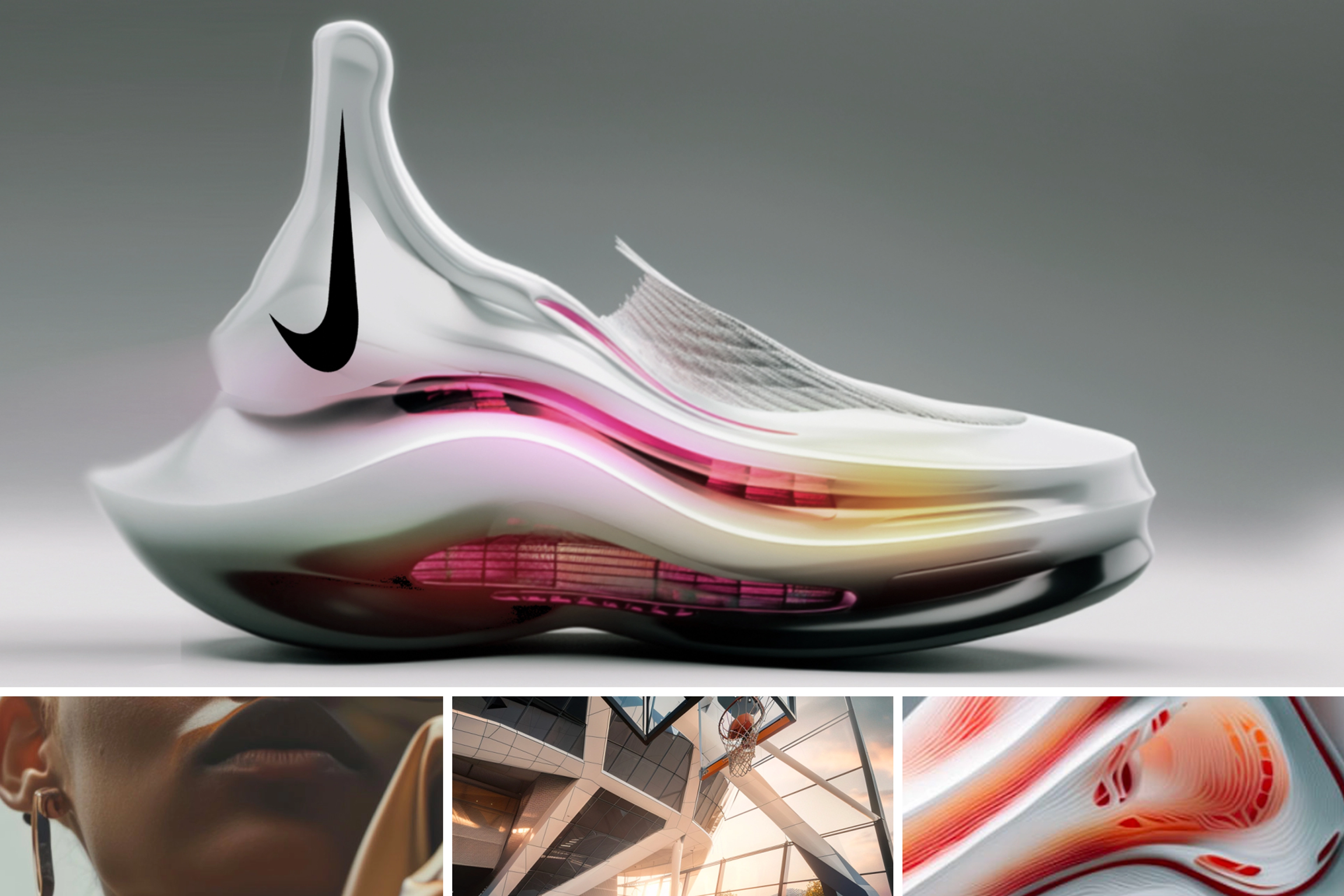

The shoe looks as mind-bending as the 7’4” forward himself. Its upper is embedded with a tight, brain-like geometric pattern, inspired by the bismuth crystal Wembanyama wore around his neck on draft night last summer when he was picked No. 1 in the league. Across the lateral midfoot and down the outsole run a fissure-shaped Nike Air unit never before used in a basketball shoe, like a crack in a comet that fell to Earth. Here, the Air unit is being used not only for cushioning underfoot, but also to forgivingly contain Wembanyama’s feet for sharp movements side to side during gameplay. Much like its athlete, every feature of the prototype is subversive. Nothing quite like it has ever been made. But it still needs refining — and fast.

Members of the team share detailed feedback with each other on the giant prototype, which is cast in a Sail color and is punctuated by hits of quintessential Nike Total Orange for the Air unit. The designers want to accent the unit with a darker gradient to highlight the jewel-like textures inside the orange. Someone notices that the pattern’s tread depth is slightly too shallow for this prototype, and the drop shadow over the texture doesn’t catch the light.

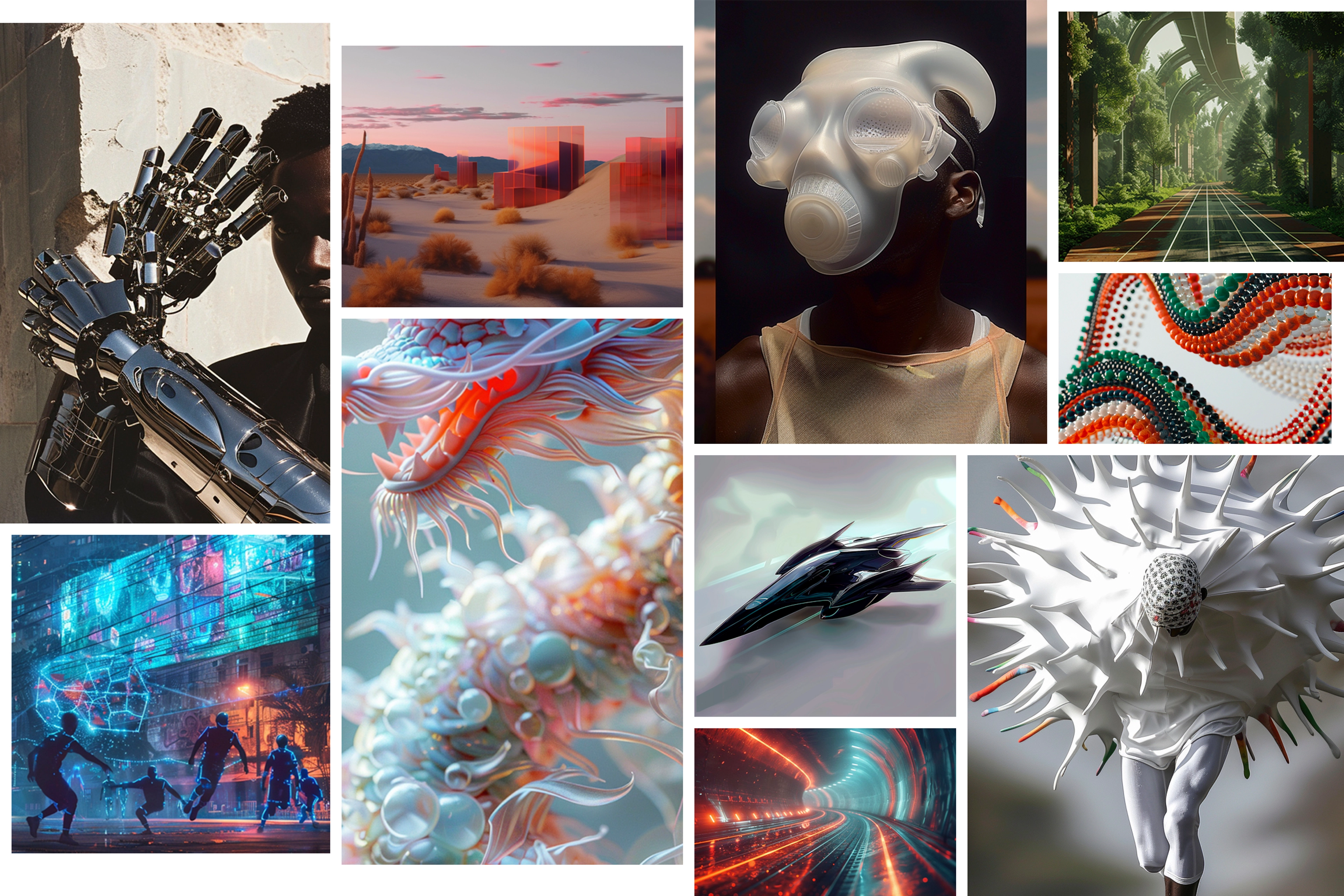

“Can we print out a new version of this Air unit?” one of the designers asks. “And can we deepen this tread?” A project manager jots down notes before rushing across the hall to the Concept Creation Center to program the changes into a large 3D printer. The chatter from 12 other shoe design review sessions hums in the giant room behind him. Surrounding the room are 13 giant mood boards, each one devoted to a different athlete’s prototype, with digital renderings and sketches and material samples practically spilling over the 8-foot tall boards.

"What I really hope this project stirs up is a sense of unlimited potential."

John Hoke, Nike, Chief Innovation Officer

The design studio in the LeBron James Innovation Building has been the incubator for A.I.R. — Athlete Imagined Revolution — a new co-creation process between teams of Nike designers and innovators and 13 of the brand’s elite athletes, from Wembanyama to Sha’Carri Richardson to Kylian Mbappé. A.I.R. brings together some of the world’s best athletes and Nike innovators and the most cutting-edge technologies, amplified by AI, to co-create the future of Air.

Perhaps no project in Nike’s history has united so many next-gen disciplines to create a new working process among designers, athletes and technology. Using Nike Air as the canvas was the perfect choice. The beauty of Air is that it will never reach its final form. It represents constant reinvention and never-ending progress. And with the advent of expanding technologies, some of Air’s wildest ideas are no longer fantasy. As the world prepares for Paris, the moment was right for Nike to envision a new frontier of Air, partnering with athletes to let their imaginations run wild.

“For these prototypes to be successful, they must stir emotions,” says John Hoke, Nike, Chief Innovation Officer. “They must evoke a sense of awe for what lies just beyond the horizon, an optimism for the future. What I really hope this project stirs up is a sense of unlimited potential. Nike Air is a nearly 50-year-young technology. We’re only at the cusp of harnessing Air’s potential, its full expression. And these footwear prototypes show we’re nowhere near done.”

The A.I.R. design techniques used in this building — known as the epicenter for advanced creation at Nike’s World Headquarters —stretch the furthest ends of computational power, the sharpest edges of manufacturing capabilities, and the most inspired touch of human craft. The prototypes showcase the imaginative possibilities for Nike Air but are grounded in a specific reality — the world in which the athlete performs and competes.

A.I.R. is creating a new definition for craftsmanship at Nike: combine the expertise of top creative talent and the most cutting-edge design tools to serve athletes at a specificity never achieved before.

A small sampling of the hundreds of concepts created by a layered range of generative tools — all in a single afternoon.

To kick off, Nike innovators organized into design teams for the 13 Nike athletes across four sports: track, global football, basketball and tennis. As with anything at Nike, the first move was to listen to the voice of the athlete. The teams approached their athletes with a searching list of questions for their ideal footwear designs. Did they want something conservative or wild? A holistic design or something defined by an individual component? Something monolithic or fractal? Other questions tapped into the athletes’ backgrounds. What people, places or things inspired them? How could the shoe practically embody the athlete? Their personality, their playing style, their physical presence. Everything. Nothing was off limits in these listening sessions.

That embodiment means tapping into the “athlete’s truth,” says Roger Chen, Nike VP, NXT, Digital Product Creation — an almost cellular understanding of the design that helps an athlete think, feel and perform at their best. Chen says the phrase served as the cornerstone for the entire design process. When a sprinter lines up for the 100-meter and she feels a soul-deep confidence that every element, including her spikes, has prepared her to win — that’s the athlete's truth, he says. And it’s a data point that can’t be quantified and requires extreme trust from both sides.

“Getting to an athlete’s truth requires authentic relationships,” says Chen. “You need to know who you’re serving. At Nike, everything hinges on how well we know our athletes.”

Once designers compiled the athletes' answers, they entered them iteratively through detailed AI command prompts to refine their ideas. After the command prompts ran their course, the output was overwhelming: hundreds of examples of AI-created visuals for each athlete, all created in an instant, to give Nike designers plenty of inspiration points for what would become the 13 final prototypes.

For Chen and his team, AI-generated outputs became tools to help deepen relationships with athletes in a faster, more specific way.

“AI exponentially increases our creative process,” says Chen. “Creating these starting points used to take us months to do. Now, we can create them in seconds. We liken AI to a sharper, more intelligent pencil. The designer is still in control. It’s what you do with the pencil that creates the magic. We gave these generative programs entire worlds to reflect back to us, and they did that. But that doesn’t happen without the thorough listening sessions our teams conducted with our athletes.”

After taking stock of the hundreds of AI visuals, the teams put the intelligent pencil down and did what they do best: design to the exact specifications of championship athletes. The 13 teams used the forms, textures, generative figures, and even the entire worlds of the AI images as inspiration to zero in on three radical shoe concepts that manifested a new expression of Air, which was easier said than done. In some cases, designers had to work against the bias of the AI algorithms to create homogenized concepts surrounding Air.

“We noticed that a lot of the AI images interpreting Air were bound by a similar fluid aesthetic,” says Chen. “The programs tend to naturally express Air as more organic, more flowy. We focused on the inspiration points that would push each concept in a specific, distinct direction.”

After designers land on the three concepts, now comes the ultimate feedback — the athletes' assessments. Every detail of the concepts was discussed, including features they’d like considered for aesthetic, functional or expressive reasons.

Chen recalled an early session the team had with Eliud Kipchoge as the marathoner gave his feedback on an initial concept. The shoe had a scooped, beveled heel carved out at the end, resembling a carbon spring on a racing flat. On paper, the aerodynamic design seemed like a sure bet.

After quietly studying the digital rendering, Kipchoge took out a sheet of notebook paper and started making his own sketches.

Kipchoge drew a version of the concept himself but added a twist. He asked the team to connect the caved-out area toward the heel. His reasoning was that the debris from unpaved trails would catch in the spring-like shape of the platform while he ran, says Chen. “He saw problems in how his shoe would operate in his training environment that we hadn’t yet considered."

Innovative design happens when every player — designer, athlete and AI — can challenge unintended assumptions. When Chen and the design team were listening to feedback from 100-meter champion Sha’Carri Richardson on her concepts, a descriptive word she used for her design hung in the air: graceful.

“When you think of Sha’Carri, you think of strength, power and determination,” says Chen. But when the design team talked to Sha’Carri about her concepts, she told the designers she didn’t want a spike that looked like a battle sandal. “Her dream was for her foot to have this oneness, this harmony with the plate construction of the spike, which is why we focused on the underfoot unit beautifully blending into the upper and up the leg sleeve,” Chen says. “It was a great example of how our athletes embody so many traits at once. We wanted their prototypes to do the same.”

“A beautiful part of the project was getting such diverse minds all around the table creating together...It’s the Nike way of uniting different disciplines to create something new.”

Roger Chen, Nike VP, NXT, Digital Product Creation

As the designers received feedback from the athletes, the next step was to make it real. The teams dove into the meticulous work of creating the prototypes through their disciplinary expertise, an instinct that the team calls “an intuitive read.”

Many of the inspiration points kicked back through the AI programs are laughably wild. If they were translated into a prototype, the shoe would never hold up to the rigors of a three-hour tennis match on a sweltering Melbourne hard court or the 360-degree movements of an exhausting full-court NBA game. Does this read like a basketball shoe? The designers are tasked with asking, if not, why not? Conversely, a successful prototype, flickering with potential to become a real performance product, made the teams ask themselves, if so, how so? What insights from A.I.R. could someday help shape future product? To get the answers, the teams tapped every advanced tool at Nike’s disposal to create the prototypes, like immersive 3D sketching, computational design and 3D printing and simulation, along with traditional methods like hand sketching.

Take paralympian and tennis player Diede de Groot. Diede needs her feet to be locked into her wheelchair, and her shoes can’t be a distraction from her game. The team couldn’t use Air as underfoot cushioning in the traditional sense, but the expression of Air still needed to be authentic to her vision. The solution: design her shoe to quickly and easily clip into her wheelchair and lock her in, similar to a cycling shoe, while using Air on the upper to provide the containment she needs. Digital methods like simulation allowed designers to test the support, containment and durability of de Groot’s shoe computationally before a real prototype was even printed.

“A beautiful part of the project was getting such diverse minds all around the table creating together, layering different techniques and technologies over one another,” says Chen. “We were constantly learning from each other. It’s the Nike way of uniting different disciplines to create something new.”

Nike’s manufacturing power gave the teams the ability to produce physical components quickly to evaluate design forms in person, in real time. This is when the full horsepower of Nike’s facilities is on display, from rapid 3D printers in the Concept Creation Center that verify design theories to Nike’s Air MI machines — located in a building a mile away from the World Headquarters — that can mold a never-before-seen Air unit proposed by an athlete.

Manufacturing added another benefit to the design process: seeing subtle imperfections within the real object that can then be improved.

Tennis pro Zheng Qinwen’s concept was inspired by her Chinese heritage, with Nike Air appearing in the form of a coiled dragon to provide support and containment, the dragon scales acting as a durable traction design.

Back in the workspace, a designer holds up Qinwen’s sample, the light above the table illuminating the Total Orange of the serpentine Air unit. The indentations of the clip, an arrangement of dragon scales made to perform like traction, perfectly line up to the geometry of the Air unit beneath, a feature that’s clear only when examined up close.

In an earlier prototype, the textures of the clip didn’t mirror the textures of the unit underneath, so Nike’s computational designers made a new sample and went deep on the pattern so the scales matched the geometry of the unit perfectly. Plus, the pattern was computationally reinforced in high-wear areas, an insight that followed extensive tennis wear-testing data pulled from the NSRL.

“Not many people will see the level of obsession that goes into these final designs,” the designer says. “The important thing is that we did it.”

The Final Athlete Concepts

The process repeats itself, with designers collecting more feedback on the samples, refining the prototype’s details, printing more components, and going back to the drawing board when needed. Mood boards in the workspace showing an athlete’s latest samples are taken down and built back up with updated renderings and materials in just hours. At the end of an unprecedented timeline, the Nike A.I.R. prototypes are ready to be revealed in Paris. It’s the textbook definition of the iterative process. And it also signals the creative process, each form a piece of stone being chipped away from all sides to reveal the art underneath.

For Hoke, from the minute the project was briefed, it always carried a vision as lofty as its A.I.R. acronym. Athletes are at the core of who Nike builds for, says Hoke. Imagined is the inspiration Nike gleans from AI as a partnering tool. Revolution means exactly that: a revolution for how Nike works.

“Our mastery of our generative tools allows us to hear athletes with a specificity that’s unmatched,” says Hoke. “In unskilled hands, AI can create designs that are full of generalities. But after listening to our athletes, we harness the conceptual power of AI and use it to get at the heart of what an athlete needs, creating a new working process. We can obsess over a product, and AI becomes a creative co-conspirator with us.”

In fact, Hoke says that emergent tools like AI give Nike designers the ability to go beyond listening. He calls it parametric innovation, a spin-off of parametric design. Algorithms churn out raw concepts based on inputs — and then the process stops. Here, the relationship between human and machine becomes linear and transactional, almost like a baton handoff in a relay race. A.I.R. challenged Nike’s design teams to create new, iterative relationships with their generative tools, sharpening inputs between program and person, refining a shoe’s features until it channels the athlete’s core being.

Hoke agrees that listening with unrivaled specificity begins with relationships, which Nike has been clear on since the company began more than 50 years ago. What is new, and at times breathtaking, he says, is the “velocity and the fidelity” with which Nike designers can create by combining AI and their relationships with athletes. The future of design at Nike is not its tools. It’s Nike’s relationship to its tools, and the bridge those tools build to deepen the relationship between athlete and designer.

On April 11, the 13 reality-bending prototypes were displayed on lit pedestals as a climactic reveal at the Nike On Air event. But Hoke was right. A.I.R. is just getting started.

“There’s no going back,” he says. “Form and function — meet fantasy.”