How Steve Prefontaine Set the Pace for Nike

- May 30, 2025

Editor’s Note: Fifty years ago today, Steve Prefontaine died in a tragic car accident at the age of 24. Kenny Moore, the esteemed writer and UO runner, said the following at his memorial service: “[Pre] conceived of his sport as a service, in the way an artist serves. Without that, he would never have given us all the records. They were out beyond winning or losing, which a runner does for himself. They came from those furious minutes near the end of a race when his relentlessness and our excitement blended into a joyous thunder. All of us who now say, ‘I had no idea how much this man meant to me,’ do so because we didn’t realize how much we meant to him. He was our glory, and we his.” Fifty years later, we remember the magic of Pre, who taught us that transformation — not just victory — is at the heart of sport.

In 1973, two years after the Nike brand was born and the first Swoosh adorned shoes, the nascent footwear company signed its first star runner. The phenomenal Oregon native held multiple American distance records, competed on track and field’s greatest stage in Munich in 1972 and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated as “America’s Distance Prodigy.”

The prodigy was Steve Prefontaine, America’s best-known track and field athlete at age 22. He possessed warrior determination and ran each race as if his life depended on it. His competitive fire, gutsy race tactics and inherent charisma charmed crowds and inspired up-and-coming runners to stick with the sport and give it their all.

“Some people create with words or with music or with a brush and paints. I like to make something beautiful when I run. I like to make people stop and say, ‘I’ve never seen anyone run like that before.‘”

Steve Prefontaine

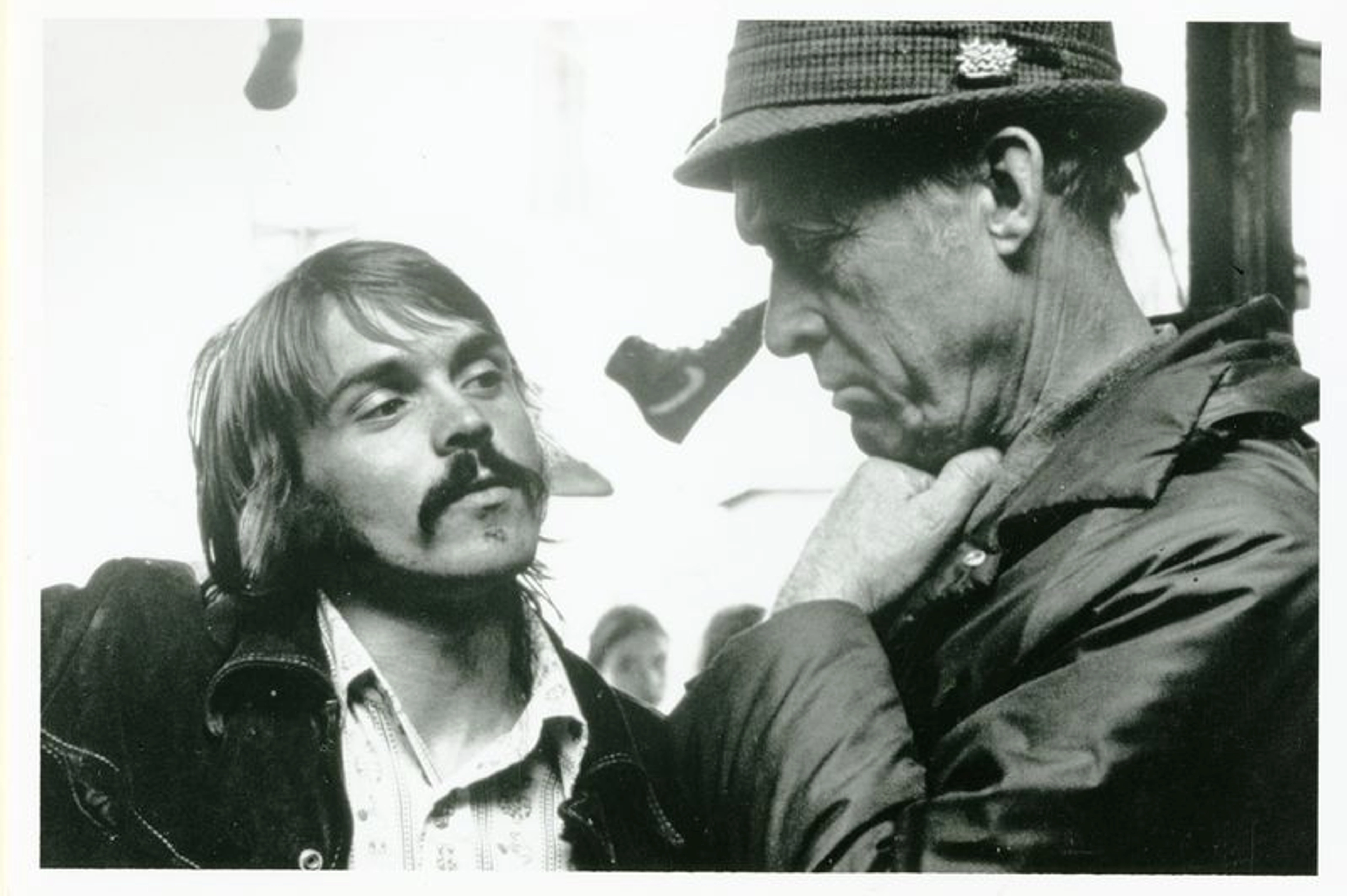

At 15, competing for Marshfield High School in in Coos Bay, Ore., Prefontaine set his first national record, running the 2-mile event in 8:41.5. He won back-to-back state cross-country championships in 1968-1969, and went undefeated in cross-country and track his junior and senior years. Heavily recruited by top running schools during his senior year, Prefontaine was swayed by a handwritten note from University of Oregon head coach Bill Bowerman. “It said if I came to Oregon, he’d make me into the best distance runner ever,” Prefontaine recalled. “That was all I needed to hear.”

Heavily recruited by top running schools during his senior year, Prefontaine (left) was swayed by a handwritten note from University of Oregon head coach Bill Bowerman (right).

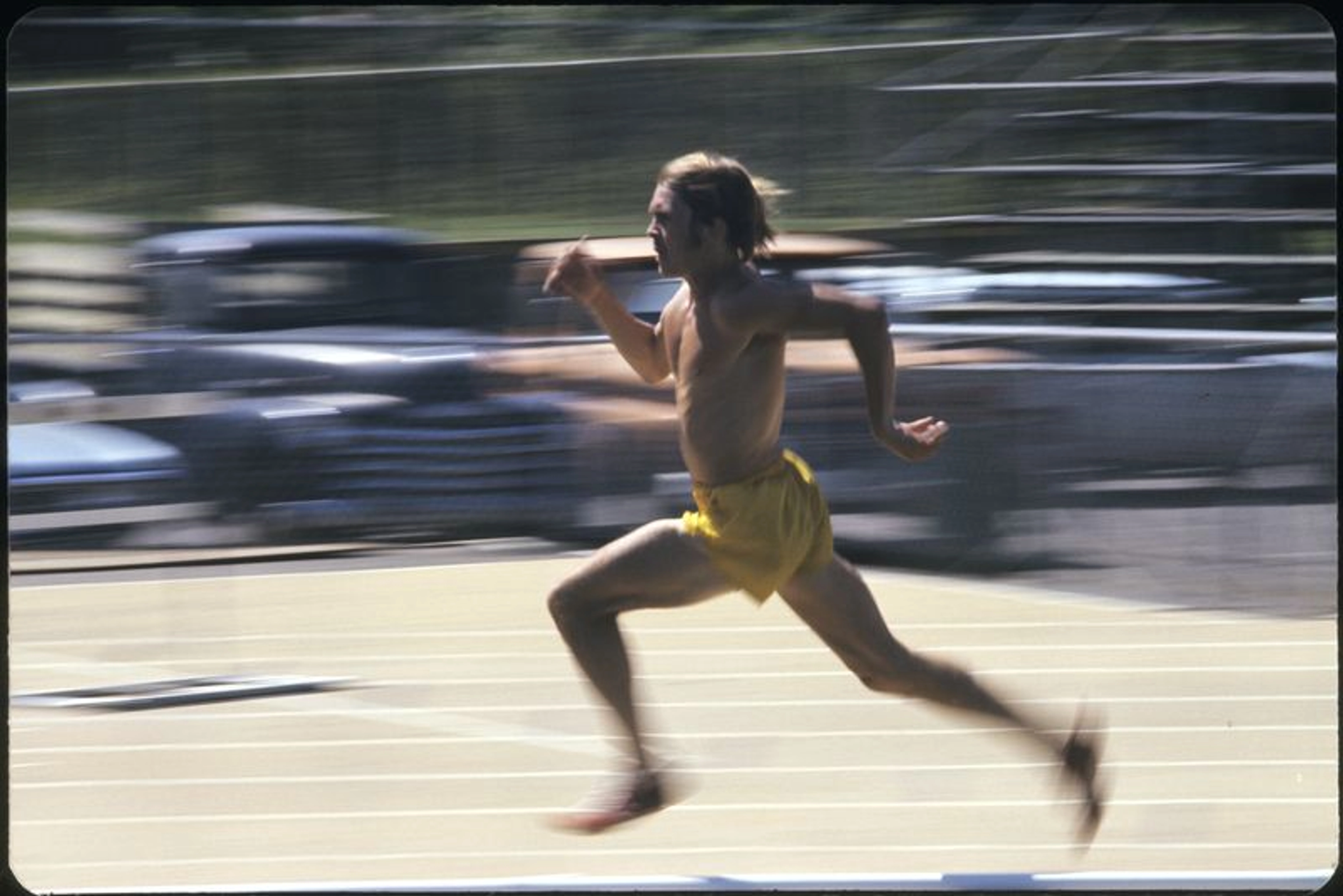

While training under Bowerman and assistant coach Bill Dellinger at Oregon beginning in 1969, Prefontaine won seven NCAA titles (three in cross-country, 1970-71, ’73; and four in the three-mile distance in track, 1970-73). In Pac-8 Conference track competition, he won three-mile titles each of his four years at Oregon, plus the mile in 1971. At home at Hayward Field during his collegiate career and beyond, he notched a remarkable 35 out of 38 victories between 1970 and 1975.

“I don’t go out there and run,” Prefontaine once remarked. “I like to give people watching something exciting.”

Prefontaine’s ascendance came at a time when running was far from mainstream. Drivers unwilling to share the road routinely yelled and threw garbage at runners as they sped past. Prefontaine helped changed that attitude from annoyance to admiration. On the strength of his indisputable achievement and winning personality, he was the first person to make running cool. His association with Nike helped establish the Swoosh as a trusted running brand and transform the company from national shoe distributor to worldwide brand.

Prefontaine won seven NCAA titles (three in cross-country, 1970-71, ’73; and four in the three-mile distance in track, 1970-73).

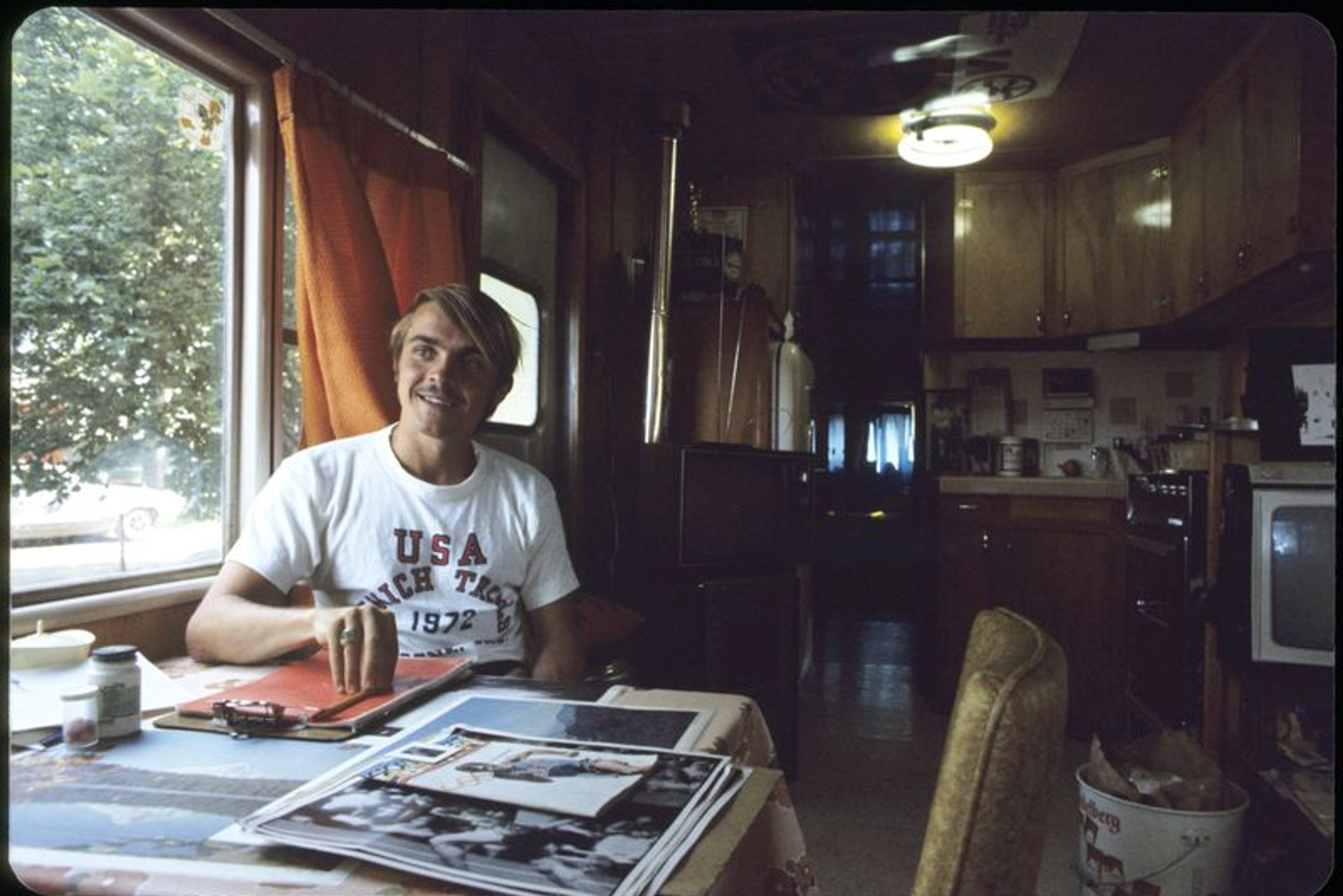

As a competitor at the University of Oregon, Prefontaine had considerable exposure to Blue Ribbon Sports and Nike footwear (at the time, products were branded Nike but the company name was still the original Blue Ribbon Sports, or BRS). In the summer of 1973, Nike co-founders Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman extended a $5,000 yearly stipend to help offset Prefontaine’s training expenses and to relieve him of occasional bartending shifts at the popular Paddock tavern.

In between track workouts and long runs along the McKenzie River, Prefontaine put in time at the BRS store in Eugene. Prefontaine became well versed in BRS and its products and he was an ace pitchman. He printed up business cards with the title National Director of Public Affairs, and began traveling around the Pacific Northwest sharing training tips and encouragement to athletes while introducing them to new Nike running shoes.

“The amazing thing about Pre was he was a hell of a student of the sport and he just loved digging and learning about things,” said Geoff Hollister, a runner who also competed at the University of Oregon under Bowerman and became Nike’s third employee. Hollister managed the BRS store in Eugene, and he and Prefontaine became close friends who shared interests in architecture, sports cars, and, of course, running.

The pair visited high schools, colleges, sports stores and running clubs. “Every place we went, Pre would take time to go for a jog with the kids. He would analyze their form, and talk to them,” Hollister said. Prefontiane easily related to teens and was a natural spokesman for the sport. In his book “Out of Nowhere,” Hollister remembered a talk Prefontaine had with students at West Albany:

“You’ve got to have goals, and I suggest you write them down. If you write them down, you own them. Don’t waste your time,” Prefontaine advised. ‘To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift.”

Prefontaine took that same personal approach when connecting with athletes from afar, helping to create an early blueprint for Nike’s sports marketing. He introduced the sport’s elite to Nike products, sending shoes, along with personalized notes and his business card, to running friends around the world. “It was totally his own idea,” said Hollister. Prefontaine shipped boxes to Mary Decker in San Diego; New Zealand’s John Walker and Dick Quax; to Brendan Foster in England; and Kenya’s Kip Keino. “All those people ended up wearing Nike shoes,” said Hollister.

In April of 1975, Prefontaine sent a note and a pair of ’73 Nike Bostons to the relatively unknown runner Bill Rodgers. The shoes' arrival created a stir among his teammates at the Greater Boston Track Club. “You’d hear about Nike shoes or see pictures, but it was the first pair that I’d seen in person,” recalled Alberto Salazar, who was a high school student in Boston and a teammate of Rodgers at the time. “He brought them to the track, and we were all holding them and passing them around. Everyone was real excited not only because it was a Nike shoe — which was kind of neat because it was different — but because Steve Prefontaine had sent the shoes with a note.” A few weeks later, Rodgers wore them in the local city marathon. He finished first.

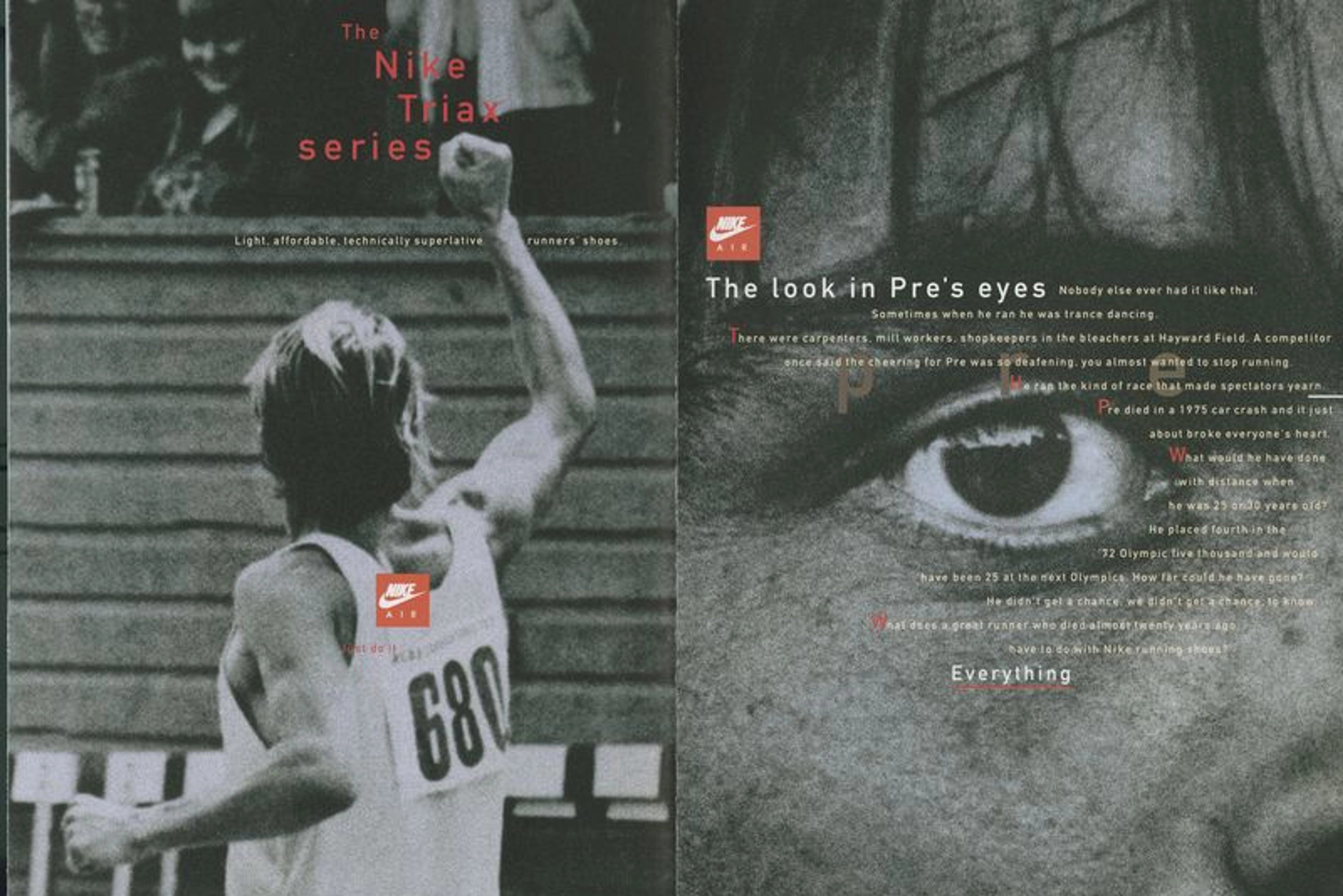

For Nike, Prefontaine was both a muse on the track and a trailblazer who pioneered a highly original and personal way of inspiring athletes with the brand.

Prefontaine is also remembered for furthering the cause of American amateur track and field athletes, who were boxed in by the lopsided rules of the American Athletics Union (AAU). In the 1970s, athletes who wanted to participate in the Olympic Games were required to remain amateurs, making it difficult but necessary to train at their sport and earn a living doing something else. The AAU controlled runners’ competition schedules and took the lion’s share of appearance fees due to athletes. Prefontaine gave up offers upwards of $200,000 to go pro to preserve his eligibility for Montreal 1976, and instead collected a $3 per diem — the maximum amount allowed by the AAU.

"Amateurism should have been kicked out in 1920,” Prefontaine said. “The average athlete now is finding it damn hard to make it."

He continually challenged the AAU and spoke out about the inequity, even when it put his eligibility to compete in jeopardy.

Prefontaine preserved his amateur status but he never made it to Montreal. His last meet was May 29, 1975, in a race he helped organize against members of the Finnish national team and distance heavy hitters such as Frank Shorter. Competing in the 5000m, Prefontaine trailed Shorter the first two miles, then, with three laps to go, accelerated to a 63-second pace. In front of a Hayward Field crowd of 7,000, he finished with a 60.3 last lap and a winning time of 13:23.8, just off his own American record.

He ran a victory lap, attended the University of Oregon track and field awards banquet and spent the rest of the evening hanging out and celebrating with friends. The biggest track and field star in the country came to a tragic end later, just after midnight, while driving home, his life cut short by a car accident at age 24.

His legacy is multifaceted. To generations of athletes at all levels, he embodies the philosophy of training incredibly hard and going all out in competition. For Nike, he was both a muse on the track and a trailblazer who pioneered a highly original and personal way of inspiring athletes with the brand. For fellow runners hamstrung by the AAU, Prefontaine was a leader who helped turn the tide towards professionalism.

After Prefontaine’s death, others joined Nike in taking up his cause, ultimately leading to the abolishment of the AAU by the U.S. Congress in 1978. It was perhaps his most important legacy off the track.

“Pre was a rebel from a working-class background, a guy full of cockiness and guts. Pre’s spirit is the cornerstone of this company’s soul.”

Nike co-founder Phil Knight