Bill Bowerman: Nike's original innovator

- 02 July 2024

In the late 1950s, veteran athletics coach Bill Bowerman was dissatisfied with available running spikes, which were made from weighty leather and metal. As a result, he became obsessed with shaving weight off the shoes to help runners slash seconds off their times. His quest wound up redefining athletic footwear.

Prior to this feat, Bowerman's drive and relentless curiosity had precipitated a string of diverse accomplishments: born in 1911 in Portland, Oregon, he excelled as a student-athlete while attending the University of Oregon and later gained acclaim as a high-school American football and track coach. He fought in World War II and came back a decorated hero. In 1948, Bowerman returned to his university alma mater and, during his 24-year tenure, led the university to four NCAA track titles and coached 16 sub-four-minute milers. He also introduced jogging to the community of Eugene in the 1960s, which helped spark a national phenomenon, and he served as the US Olympic track coach in 1972.

"A shoe must be three things: it must be light, comfortable and it's got to go the distance".

Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman

Bill Bowerman with an Oregon track athlete circa 1969.

Bowerman was also a mentor, coach and friend to Phil Knight, with whom he co-founded Blue Ribbon Sports, the precursor to Nike, in 1964. His confidence and counsel helped the company's original business model—importing and selling Japanese-made running shoes —to succeed and grow.

However, Bowerman's own footwear innovations proved even more influential, shaping Nike's ethos of leveraging athlete insights to design transformative products.

Bowerman first began tinkering with running shoes in the 1950s, when he wrote to several footwear companies proposing ideas for improving shoes to better serve runners. None accepted his recommendations. Frustrated but not deterred, Bowerman took matters into his own hands and, with the guidance of a local cobbler, learnt how to make shoes. To start, he deconstructed existing racing shoes with his band saw and examined their anatomy. Then, he toyed with metal and plastic spike plates and assembled various uppers over diverse lasts. Later, a Springfield-based boot maker provided technical advice and showed Bowerman how to craft shoe patterns.

Bill Bowerman and Phil Knight at Oregon.

Phil Knight became the first student-athlete to try a Bowerman original. In a letter to Knight dated 8 August 1958, Bowerman suggested a weight-training programme and running schedule. He closed the letter with a postscript: "If you have a pair of shoes that you think would make good flats, send them down to me. They will be ready for you when school starts". Bowerman fitted a handmade pair with an upper made from white rubber-coated fabric—"the kind you'd use for a tablecloth you could sponge off", he explained—to Knight's size. Knight says Bowerman chose him to try the shoes because he "wasn't one of the best runners on the team. Bowerman knew he could use me as a guinea pig without much risk".

Whatever the reasoning, the young runner tested the shoes at training one evening but didn't get to wear them for long. His teammate Otis Davis spotted the prototype and wanted to give it a try. He liked the shoes so much he didn't give them back. In fact, Davis went on to win a conference championship and a gold medal in the 400 metres at the 1960 Olympic Games in Bowerman-made shoes.

Moving forwards, Bowerman custom fit shoes to his runners by drawing an outline of their feet, measuring widths and noting individual features, such as an extended heel or slim ankle. He experimented with dozens of textiles—kangaroo leather, velvet, deer hide, snakeskin and even fish skin—to find the ideal lightweight, stretchy and resilient material, churning out new creations on a weekly basis. As his prototypes grew more refined and reliable, he continued to seek alliances with footwear companies, to no avail.

In an August 1960 letter to a Portland company requesting steel for spikes, Bowerman wrote: "Most American shoemakers are not interested in what we track coaches think about track shoes. The best shoes … at this time are made by the Germans. Their sole material is not too good, and I can either replace their sole or I can make my own shoe. I don't think there is any question, certainly in my own mind there is not, that I now have the best shoe in the world—if I could just find some good American shoemaker to make it".

This opportunity finally arrived when Knight forged a relationship with Onitsuka in 1964, based on the belief that less expensive Japanese-made running shoes could perform as well as standard-bearer German shoes. Subsequently, he and Bowerman invested 50–50 in the business of importing and selling running shoes, opening a path for Bowerman's own ideas. The coach expressed his optimism in a letter to Onitsuka in May 1964: " I hope that your arrangements with Mr Knight would be such that I would be free to turn over the ideas that I have worked out on track shoes ".

Bowerman spent the following summer designing and in October travelled with his wife, Barbara, to Tokyo for the 1964 Olympics Games, where three of his Oregon runners were competing. The couple stayed an extra week so that Bowerman could meet with Onitsuka founder and CEO Kihachiro Onitsuka as well as S Morimoto, a company executive. Bowerman explained his ideas and toured factories to study the cutting and stitching machines. He gained confidence in the Japanese shoemaking process and established relationships with the two leaders, ensuring a receptive audience for his future prototypes and suggestions.

"He thought running shoes could be better. He challenged accepted notions of traction, cushioning, biomechanics and even of anatomy itself".

Jeff Johnson, Nike's first full-time employee

Bowerman's first breakthrough with Tiger shoes surfaced the following spring, in 1965, as the indirect result of an athletics competition. At the competition, University of Oregon distance runner and future Olympic marathoner Kenny Moore moved wide in an 880-metre race, into the path of a passing teammate. The misstep resulted in a spike-inflicted gash on the outside of his foot. That injury led to a stress fracture and one of Bowerman's most enduring inventions.

Early in Moore's recovery, the runner trained in the Onitsuka Tiger TG-22, a high-jump shoe that Blue Ribbon Sports mistakenly sold as a running shoe. When Moore's X-ray showed a break across the third metatarsal, Bowerman asked to see his shoes and promptly ripped them apart. They had spongy cushioning in the heel and forefoot but zero arch support. "If you set out to engineer a shoe to bend metatarsals until they snap, you couldn't do much better than this", Bowerman growled. "Not only that, the outer sole rubber wears away like cornbread".

To correct the TG-22, Bowerman fashioned a running shoe with a cushiony innersole, soft sponge rubber in the forefoot and on the top of the heel, hard sponge rubber in the middle of the heel and a firm rubber outsole. In June 1965, he sent Onitsuka instructions and samples for the shoe.

Kenny Moore prototype: profile

Kenny Moore prototype: outsole

A month later, Morimoto responded, confirming that he was producing a training shoe to the specifications. But, Onitsuka had "some opinion as to the inserted sponge rubber in the heel". Despite the objections, Bowerman pushed for the placement of sponge rubber in the heel, stating that it would help alleviate Achilles tendon issues. That summer, Moore rebounded from his stress fracture and logged more than 1,000 miles in Bowerman's latest creations. Early Onitsuka prototypes featured two distinct pads in the heel and the ball of the foot, and a narrow heel. This eventually morphed into the full-length midsole Bowerman had originally conceived, a feature that ultimately became a major selling point for the shoe.

Consequently, Onitsuka introduced the Bowerman-engineered Tiger Cortez, which an early 1967 catalogue explained as: "Designed to be the finest long-distance shoe in the world. Soft sponge midsole through ball and heel absorbs road shock; high-density outer sole for extra miles of wear".

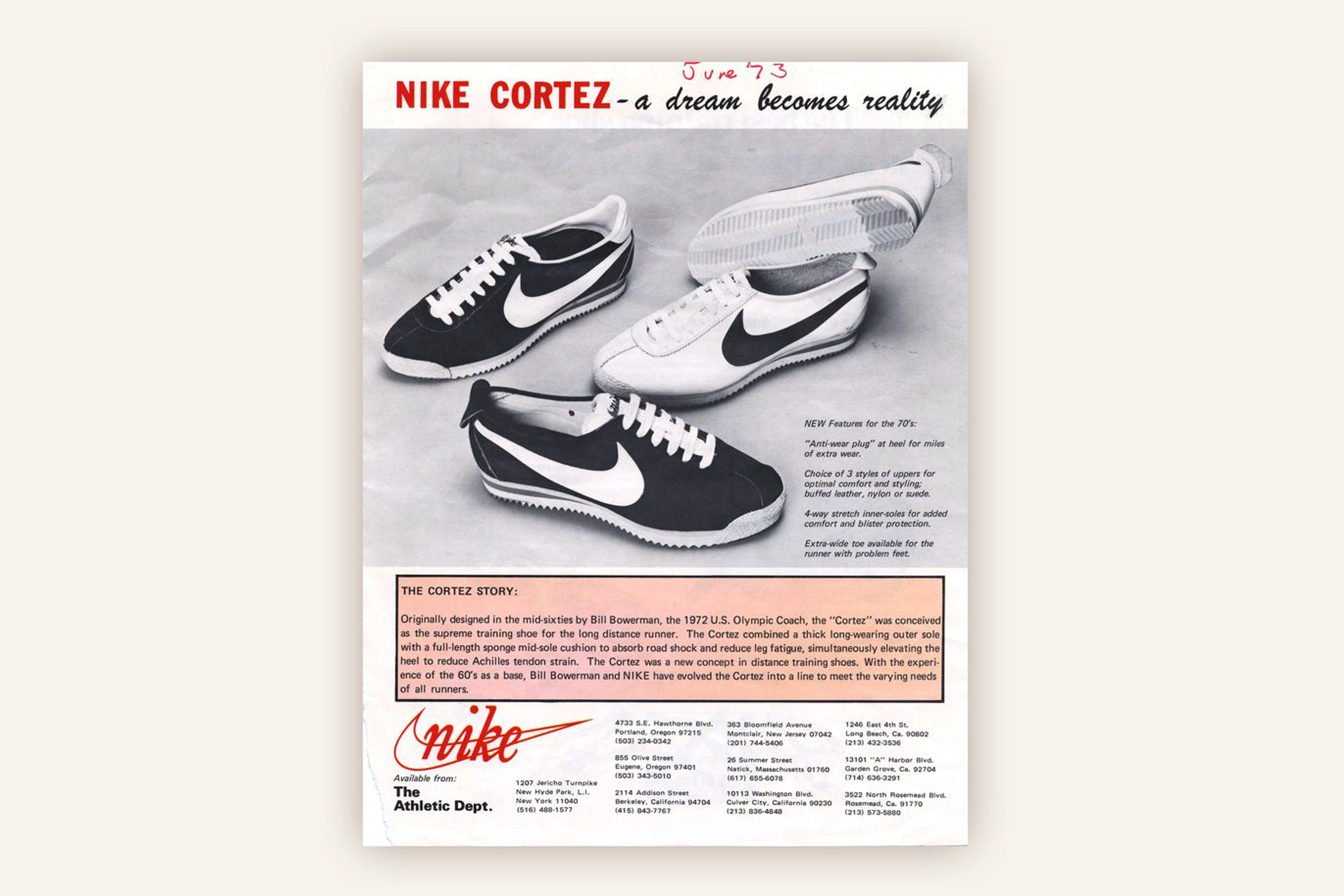

The Nike Cortez

Consumers loved it. The Cortez was the first stable, comfortable shoe for the roads. It looked cool and debuted as running emerged as an American pastime, popularised by Bowerman and his 1967 book "Jogging". And when Knight and Bowerman stopped importing and distributing running shoes through Blue Ribbon Sports and launched Nike as a designer and maker of athletic shoes, the Cortez silhouette carried over to the new brand. It also earned Bowerman a patent for its innovative continuously cushioned midsole. In July 1973, Runner's World called the Nike Cortez "the most popular long-distance training shoe in the US".

The Cortez, however, was just the first of Bowerman's celebrated inventions, which came to comprise eight registered patents, including shoes with an external heel counter, improved spike placement and a cushioned spike plate. It was also just the first success in his enduring quest to create the lightest running shoe possible.

"He thought running shoes could be better", Nike's first full-time employee Jeff Johnson says about Bowerman's early innovations. "He challenged accepted notions of traction, cushioning, biomechanics and even of anatomy itself".

Bowerman next sought to manifest a shoe with excellent traction on multiple surfaces, without metal spikes. The solution came over breakfast in 1970, as he contemplated the syrup-cradling depressions of the waffle on his plate. "What if you reversed the pattern and formed a material with raised waffle-grid nubs?", he wondered. He subsequently commandeered the family waffle maker and substituted batter for melted urethane. Unfortunately, Bowerman initially forgot to grease the waffle maker with an anti-stick agent, and it glued shut. Despite this setback, he persevered and fashioned a flexible, springy and lightweight rubber material with a raised, gridded pattern and grip traction.

The Blue Ribbon Sports crew raced to debut the Waffle sole at the upcoming 1972 US Olympic athletics trials in Eugene. They had nylon uppers flown in from Japan to pair with Waffle soles hand-cut from sheets of rubber made in Eugene. Early Blue Ribbon Sports employee Geoff Hollister glued the components together, creating shoes for a handful of trial competitors to wear during training or on the infield at the Hayward Field athletics stadium.

The hand-built shoes were dubbed the Moon Shoe due to the distinctive imprint they made in the dirt, which resembled the lunar footprints left behind by American astronauts during the era's historic Apollo missions. The first iterations were crude, but runners liked the feel and traction of the Waffle sole and word of the invention quickly spread. Bowerman further refined the concept and developed the iconic Waffle Trainer in 1974.

The rubber studs of the Waffle sole offered give and cushioning that appealed to both elite athletes and everyday runners. The shoes, as TIME magazine wrote, were "grabbed by the army of weekend jocks suffering from bruised feet". The Waffle Trainer placed Nike on the global athletic footwear map, setting the stage for unparalleled growth.

Bowerman's legacy as an original thinker and innovator will forever be linked with the Waffle sole, which like many brilliant inventions is so simple and intuitive it resonates immediately and broadly. Versions of it are still employed today in Nike footwear, as are Bowerman's many other contributions to running shoe innovation, including the raised heel, the nylon upper and the continuous midsole.

Nike's footwear ideal has evolved, but Bowerman's preoccupation with creating products that enable athletes to perform at their highest potential continues to fuel Nike's culture of innovation. Contemporary examples can be found in footwear technologies such as the Nike Free articulated outsole and the compressive woven-in support of Nike Flyknit uppers.